Book Review: Peer Coaching

by Pam Robbins

In the

Introduction to Peer Coaching, Pam Robbins laments that many teachers still

work in isolation and that digital learning “…has precipitated isolation.” (2)

Hence, there

is a need for strategies such as peer coaching.

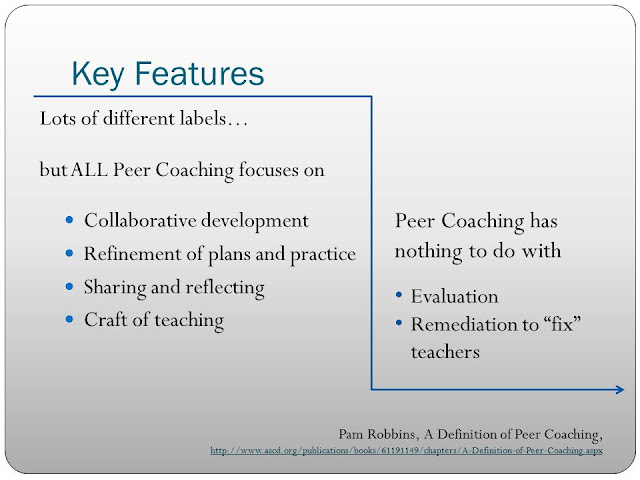

Robbins maintains that “peer coaching offers a non-evaluative,

differentiated, professional development support strategy” for teacher

collaboration. (5) She notes that

research indicates that student achievement is four times more likely to improve

in schools in which teachers collaborate than in schools where teachers work in

isolation.

In Chapter 1,

Robbins introduces the 2 branches of peer coaching. The first, collaborative work, involves a number of structures for teachers to

work together without classroom observations.

Once mutual trust and confidence in collaboration are established,

teachers can move formal coaching, which

involves classroom observation.

The

principal’s role in peer coaching and the advantages of peer coaching are also

discussed in Chapter 1. For peer

coaching to be successful, a principal should:

- Allocate sufficient time and resources to it;

- Make clear that it is not connected to formal teacher assessment;

- Coordinate schedules and substitute teachers for coaching sessions; and,

- Actively participate in peer coaching

The benefits of peer coaching include the sharing of

“well-kept secrets” of teaching practice, empowerment of teacher-leaders, and

differentiation of teacher feedback. (19)

Robbins describes, in Chapter 2, more key factors in the

success of peer coaching. Some of these

factors are PD on coaching, time for practice and reflection, and the building

of a school culture of trust and risk-taking.

One specific strategy she recommends for professional learning is the

creation of a library about coaching. (32)

Chapter 3 outlines several collaborative work structures:

- Sharing classroom success stories;

- Analyzing videos on teaching and learning;

- Engaging in group problem solving;

- Forming action research study groups;

- Having

conversations about specific student work; and,

- Co-planning lessons.

Robbins says that teachers should agree in advance to

specific protocols for any of these structures.

For instance, she recommends Consulting Colleagues for group problem

solving, whereby one teacher shares a problem, then the other teachers in the

group ask clarifying questions, and lastly, the teachers offer solutions.

The components of formal

coaching are identified in Chapter 4.

Its partners are an inviting

teacher and a coach. It involves a

pre-conference, observation, and a post-conference. The pre-conference is a sort of “dress

rehearsal” of the observation. (54)

There are 3 types of post-conferences:

- Mirroring

– the coach is a data

collector and objective observer;

- Collaborative

– there is mutual

discussion between the teacher and coach; and,

- Expert

– the coach provides

teaching.

The author concludes Chapter 4 with a few additional

considerations. First, coaching should

never be mandated. When it is, it risks

becoming what Andy Hargreaves has termed “contrived collegiality”. (59) Teachers should always choose their coaches

and have the chance to play the roles of both inviting teacher and coach.

Six principles for effective conferences are discussed in

Chapter 5:

- Use a common

language;

- Identify a specific

focus for the observation;

- Use objective data

– without interpretation;

- Allow for interaction

– There should be “a spirit of curiosity about teaching and learning”

(67);

- Predictability

– consistency between

expectations and actions; and,

- Reciprocity between coach and inviting teacher.

At the pre-conference, expectations and parameters for the

observation should be set. The inviting

teacher should also clarify learning goals for the lesson to be observed and

supply the coach with background to the lesson and the expected teacher and

student behaviours. The teacher should

also describe how data are to be collected.

Several useful tips and resources for classroom observations

are shared in Chapter 6. First, it is

important that the inviting teacher and coach agree upon a teaching and

learning model. (The author recommends

Alvy & Robbins’ Student Learning Nexus.)

The observation should centre on evidence of student learning, including

students’ responses and artifacts, and not on observation of the teacher. Including student voices – either by

video-recording or scripting – is recommended.

Robbins identifies an iPad app called Videre for labeling video clips

according to specific topics such as collaboration, feedback, and

metacognition.

The main goal of the post-conference (the subject of Chapter

7) is to promote reflection by the inviting teacher concerning teaching

practice. The coach’s approach is

conceived by Robbins as “discrepancy analysis” (95) – that is, helping the

teacher see the gaps between his/her practices and desired outcomes. To avoid an evaluative atmosphere, the coach

should conclude the post-conference by handing over the observation data and

artifacts of student work to the teacher.

Feedback by the coach should be “timely, specific, nonjudgmental,

non-evaluative … and meaningful.” (104)

In Chapter 8, the author identifies several conditions

necessary for a coaching program to be successful, including,

- A shared vision of peer coaching must be embedded in the

school culture;

- Collaboration must be a common practice;

- A high level of trust must exist among staff; and,

- Supports must be present for coaching, such as time, resources, and “administrative endorsement and advocacy” (107).

Robbins provides, in Chapter 9, suggestions to guide

principals in each of the 3 implementation phases of a peer-coaching program. In the mobilization phase, a planning

committee should be formed to develop an implementation plan. The author stresses that representatives from

the teachers’ union should be included on this committee. In this phase, information about peer coaching

should be shared with staff, including an awareness presentation.

In the implementation phase, the emphasis should be on

providing both PD opportunities and opportunities for teachers to practice

collaborative work and peer coaching. An

important aspect to include in this stage is “the coaching of [peer] coaches”.

(133) Robbins also recommends that

during this phase that a public forum (ie. a Facebook page or Google group) be

established for celebrating peer coaching successes. Her advice for principals during the

institutionalization phase is to continue to monitor, celebrate, and support

the peer mentoring initiative.

In the final chapter, Robbins provides a few cautions and

insights regarding the change process.

One such caution she offers is that change is messy and often “brings a

sense of loss” (142) for some people, so principals should tread lightly as

they introduce peer coaching.